State has $500M backlog in capital projects for parks system

State has $500M backlog in capital projects for parks system

Sylvia Kocses had a great second date in 1967 at Washington Crossing State Park with the man who would become her husband. When they had kids, the park in Mercer County became their go-to, with its playgrounds, nature center, open-air theater, and 13 miles of trails.

Sylvia Kocses of Titusville walks on Continental Lane past a tree uprooted in a storm last summer in Washington Crossing State Park in Hopewell. (Photo by Dana DiFilippo | New Jersey Monitor)

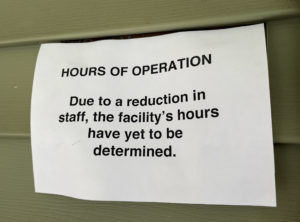

Now 71, Kocses takes her grandchildren and husband for walks there — though not so often anymore. The nature center and open-air theater have closed. Some park roads and lots are so potholed drivers have to zigzag to preserve their tires. Trees toppled by a storm last summer still litter Continental Lane, a popular nature trail where George Washington and his troops began their march to Trenton in 1776 after crossing the Delaware River from Pennsylvania.

“Why have a park that is so historically, fantastically important and not maintain it?” said Kocses, who lives in neighboring Titusville. “Everyone’s all about open space these days and the environment, and yet we have these beautiful acres of land and they’re in total disrepair.”

Washington Crossing State Park, like many of New Jersey’s 51 state parks, has grown increasingly shabby, especially in recent years as the pandemic has driven more people outdoors while state funding for parks has flatlined.

Shawn LaTourette, who heads the state Department of Environmental Protection, is well-aware of the sad state of state parks. He testified about it to state lawmakers at a budget hearing last month, lamenting a $500 million backlog in capital-improvement needs across the state park system.

“We have had to triage the issues, in terms of what types of capital investment we’re able to achieve, and focus on health, life, and safety issues,” LaTourette later told the New Jersey Monitor.

Amie Rukenstein serves on a volunteer board that supports Washington Crossing State Park. She fumes as she looks across the Delaware River, where Pennsylvania’s scenic Washington Crossing Historic Park lies.

“The Pennsylvania park is fabulous, and our park is dreck,” she said. “It’s a glaring, glaring difference.”

With the nation’s 250th birthday looming in 2026, the park expects a deluge of history buffs eager to visit significant sites.

So Rukenstein and others have launched an advocacy campaign urging park-lovers to lobby their lawmakers to support “heritage tourism.” They want the governor to include $65 million in his $48.9 billion budget proposal to repair and upgrade American Revolution sites in state parks.

Absent that, they’ve asked officials to prioritize park needs so they can fundraise to fix what the state won’t.

But while 31 other states have foundations that enable people to raise money to support state parks, New Jersey doesn’t — a shortcoming Rukenstein said shows, along with stagnant state funding, New Jersey officials’ misplaced priorities. She pointed to New Jersey’s plan to spend $65 million to buy 135 acres and create a new Essex-Hudson Greenway.

“It’s sexy to make new parks — and nothing against wanting to do that — but you can’t just make new stuff and let your old stuff fall apart,” Rukenstein said.

A study in contrasts

With its flowering trees, hilly roads, and a farmhouse dating back to 1740, Washington Crossing State Park is a picturesque, if unkempt, woodland along the Delaware River that drew more than 270,000 visitors last year.

But wander across the narrow Washington Crossing Bridge to the Pennsylvania side, and it’s like the difference between the Ritz and a fleabag motel.

The 500-acre park in Bucks County — called Washington Crossing Historic Park — has a charming historic village where reenactors do living history demonstrations, a tidy memorial cemetery where unknown Continental soldiers are buried, gardens designed to look at they would have in the 18th century, and a slick visitor’s center with a 248-seat auditorium, bright museum space, gift shop, and a wall of windows with a postcard-pretty view of the river.

Soon, it’ll be even nicer: Pennsylvania officials last year launched an $8.7 million project to conserve and improve 17 historic structures in the park.

Dolores Mita has lived near the park for 18 years.

“The Jersey side? I don’t dislike it. I just don’t get that feeling of history that I get on this side,” Mita said. “This side, to me, has a history that’s more vibrant. You can picture it.”

Besides, she added, “it’s just prettier here.”

In New Jersey, efforts are underway to improve the park in time for the Semiquincentennial. The state will spend $10 million to build a new visitor’s center overlooking Route 29. The existing visitor’s center, built about 50 years ago, will be demolished.

But the park’s needs exceed that, some say.

Staffing shortages compound its problems, with just three maintenance workers at the park, down from 43 employees at the 1976 Bicentennial, according to the Washington Crossing Park Association, a volunteer board.

John Cecil is the state Department of Environmental Protection’s assistant commissioner for state parks, forests, and historic sites.

Cecil said it’s not fair to compare the two Washington Crossing state parks, because Pennsylvania’s park is more “narrowly scoped” on history and eight times smaller than New Jersey’s park, which sprawls across 4,130 acres spanning six townships.

Besides, he said, the state has spent money — or plans to — in Washington Crossing State Park to remove hazardous trees, improve a park police office, upgrade water and HVAC systems, and replace playgrounds.

But he’s also “keenly aware” lots of other needs exist — and are going unfunded — in both Washington Crossing State Park and all state parks.

“We are trying aggressively to address it while recognizing we have a network of parks across the state on 450,000 acres of land that is being challenged by climate change and by greater visitation during this global pandemic,” Cecil said.

Busier parks, same need

The state’s busiest parks tend to get more support, LaTourette told the New Jersey Monitor.

“Washington Crossing is not one of the highly trafficked parks,” he said. “As a function of that, it may end up lower down in the matrix in terms of what investment is going where.”

Liberty State Park is New Jersey’s busiest state park, drawing more than 5 million visitors a year to its 1,200 acres, which are split evenly across land and water.

Sam Pesin’s father founded Liberty State Park, which opened in 1976. Pesin is the longtime president of the all-volunteer Friends of Liberty State Park.

He can tick off plenty of unfunded needs at Liberty State Park, like erosion of park jetties and the park’s historic Morris Canal and asbestos that contaminates the train shed over tracks that were a transportation hub for centuries. He’s reluctant to go on, because he knows those who want to privatize portions of the park for profit would cite such needs — and the money commercialization might generate for the park — as a reason why the state should allow them to develop parts of the park.

Pesin has been fighting park privatization for years, most recently through a stalled billcalled the Liberty State Park Protection Act that would restrict commercialization there.

He shouldn’t have to wage that fight, he said, calling on lawmakers to both pass the act and increase park funding.

“Why the hell is there a $500 million backlog? That should be addressed as soon as possible and in a major way,” Pesin said. “The elected officials are always saying how much they love state parks. They should put their money where their praises are. It’s just overdue for the Legislature to drastically increase funding for all state parks.”

Foundation an answer?

LaTourette said he gets it. He’d like more funding not only for state parks, but for his department in general.

But he didn’t push for more when he testified in a Senate budget hearing last month. In an interview earlier this month, he told the New Jersey Monitor the state has so many competing needs the governor faces “seemingly impossible choices.”

Marci Mowery heads both the National Association of State Park Foundations and the Pennsylvania Parks and Forests Foundation.

Park funding isn’t a high priority for legislators in many states — but it should be, Mowery said. “Parks are big business. They attract people, they support quality of life, they’re a way to recruit business and industry to come in. They help improve human health. And during the pandemic, we saw how important access to the outdoors was for so many people,” she said.

Parks also offer environmental benefits, such as flood reduction, water quality improvement, and air quality improvement, and postponing repairs is “not sound financial management,” she added.

“When we kick the can down the road, it becomes more expensive,” Mowry said. “When we don’t put the roof on a building, we may then have to repair the ceiling and replace the furniture and the floor.”

So much need

New Jersey’s snub of its historic sites has long been a frustration.

Some of the projects that have lingered the longest on state parks’ to-do list are historic restorations and visitor centers, LaTourette acknowledged. They include an educational center for visitors at Princeton Battlefield and restoration work at the Indian King Tavern in the Brendan Byrne State Forest, Monmouth Battlefield State Park, and the grist mill at Batsto Village in Wharton State Forest.

Shawn LaTourette, commissioner of the New Jersey Department of Environmental Protection, testified before the Senate Budget Committee on April 26, 2022. (Photo courtesy of New Jersey Senate)

“We can’t take care of everything. We’ve got to do the best we can with what we have,” Spearman said. “And that’s one of the reasons for creating the foundation — to see if we can supplement the funding that we do have.”

LaTourette agrees foundations could help.

“Folks should be able to support the places they love,” he said.

Two lawmakers aim to fix that oversight and have introduced a bill to create a nonprofit foundation to support New Jersey’s state parks. Sponsors Sen. Shirley Turner (D-Mercer) and Assemblyman William Spearman (D-Camden) introduced the same bill in the last legislative session, but it failed to advance.

Kocses would be among the first jumping into action to drum up support and supplement state funding. Her husband uses a wheelchair now, so their visits to Washington Crossing State Park have grown more infrequent.

“I can push him on the road here, but part of our society today is looking for equity, especially for people of differing abilities. I think the park should address even that small of an issue,” she said. “But there are other issues, safety issues, historical issues, that are just as important.”

Without action, she added, the park will continue to decay.

“A valuable historical site that’s unique to New Jersey will be lost,” she said.

This story was produced in collaboration with CivicStory and the NJ Sustainability Reporting project.