NEWARK, NJ — An urban farm on the property of West Side High School is not only planting hope for a more sustainable future in Newark but an opportunity for students to succeed.

An urban farm on the property of West Side High School is not only planting hope for a more sustainable future in Newark but an opportunity for students to succeed. Photo credit: Tom Wiedmann

On the farm, students are learning how to grow a wide range of things, including apricot trees, collard greens, tomatoes, peppers, onions and other produce. As the district’s designated business-focused comprehensive high school, West Side is also incorporating agribusiness education into the student learning experience.

“You now have kids that are learning agriculture, know how to start this and see it come to fruition,” West Side High School Principal Akbar Cook told TAPinto Newark. “We’re showing them the whole ecosystem of how to sustain themselves, doing it healthily and teaching them nutrition.”

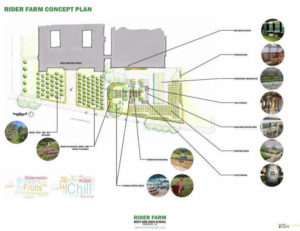

The farm already features multiple vegetable beds, fruit trees and composting. Plans are in place to set up even more components on the farm including bee hives, an outdoor kitchen area and a hydroponic greenhouse.

Initial funding for the project at West Side was backed by a $100,000 gift to Cook from Ellen DeGeneres after he appeared on her show highlighting his outreach work at the school and the greater community. To recognize DeGeneres’ contribution, the farm was aptly named “The Ellen DeGeneres Urban Farm,” with a mural on the school building showcasing the popular television host. Cook also received a $50,000 grant from L.L. Bean to back the project.

“It’s go big or go home at West Side,” Cook quipped. “We should be breaking ground soon to put up the greenhouse to do the farm on the side by the Ellen mural like it was supposed to be… My hats off to my staff and students for moving this site on the other side of the school so we could get going, but now the real project is about to start.”

Sowing An Idea

Even with the financial backing in place, the ambitious project didn’t just turn up at West Side overnight. The principal said it took several years of hard work and community partnerships.

First, Cook said he needed to come up with an idea on how to best use the money to support his students and community. Knowing the city’s West Ward was designated as a “food desert,” an area where people have limited access to fresh, nutritional foods, he consulted with educators on the creation of an urban farm and formed partnerships with nonprofit Jersey CARES, the Urban Agriculture Cooperative (UAC), and others to bring the idea to fruition.

With a plan in place, the project broke ground several years ago and was on pace for completion by summer 2020. The coronavirus pandemic and supply chain shortage issues, however, set back multiple projects on the farm. With the worst days of the pandemic, hopefully, behind Newark, the project is coming together again slowly but surely.

Emilio Panasci, co-founder and executive director of UAC, said the project at West Side, once completed, will be nearly a full acre – one of the biggest urban farms in Newark.

“The vision for it is to not only grow healthy, local food but also to have refrigeration there, tool storage, a washing station, and an outdoor classroom education area,” Panasci said. “It’s a real comprehensive food hub that’s more than just production where other activities can take place as well.”

Cultivating a Sustainable Community

The urban farm has already proven to be a tremendous success at West Side – both for the environment and the students.

Cesar Presa, the head farmer of the project, said the urban farm in 2021 produced more than 300 pounds of food. As the project expands, Presa said the goal is to produce 1,000 pounds of food this year.

“We’re only 60 to 70 percent of the way there, and we already have so much stuff,” Presa told TAPinto Newark.

Almost anything that grows on West Side’s urban farm is finding its way back into the community, too.

Principal Cook noted that prior to installing an urban farm at West Side, he was already distributing fresh food and groceries to residents in the community. Now, he gets to have a direct approach to providing Newarkers with goods grown right at West Side.

“We’re giving them some of our own fresh produce. We’re going farm-to-table,” he said.

At West Side, where many students qualify for free or reduced-price lunch and lack access to healthy meals, the urban farm is also addressing food inequity in the community. Food insecurity in minority-majority communities like Newark can be directly linked to health disparities experienced among Black and brown people such as increased rates of obesity, heart disease, diabetes, and hypertension.

A multi-state study found that only 8% of African Americans live in a tract with a supermarket, compared to 31% of white people, according to the Food Trust, a nonprofit that advocates for the improved health of children and adults.

Having students learn about agriculture and doing physical work on a farm could help not only address food insecurity in Newark but promote a more sustainable community as well.

What students learn at school can then be taken back home where they can set up small vegetable beds in their own backyard. At home, they can teach their parents and siblings how to grow food, too. As a community becomes more knowledgeable about farming, this can play a small part in tackling the city’s food insecurity issues.

“It’s about learning to be healthy through food but also understanding yourself in a social and cultural way – how you relate to your environment and the people around you,” Presa said. “Gardening and farming all lead to those outcomes.”

Alongside his daily upkeep of the farm, Presa teaches students from West Side’s environmental science classes about agriculture. He also works with a group of students during the summer months to maintain the farm.

On the farm, part of the students’ learning experience requires them to get their hands dirty. Presa said students do a variety of activities and upkeep projects on the farm such as weeding and pulling grass out of vegetable beds.

There are perks, too. The head farmer noted that students can walk through the orchard and taste-test the items growing on the farm such as chives, scallions, thyme and chocolate mint plant.

“You don’t need a large farm to do this. You just need a few beds to get the experience,” he said.

Planting Ambition in Students

Students also have a lot to gain outside the classroom from working on the farm.

One West Side student, Zhamirr Williams, had one word to describe his time working on the farm with his peers: “magical.”

“It was an emotional experience,” Zhamirr said. “[Farming] is like taking care of a baby – it’s like life. Everybody wants to grow up and mature, and that’s what plants do. They grow up, rise and look beautiful. It’s a process and I watched it happen. There was no YouTube video where you watch it grow fast. I was there to watch something grow that I put in the ground. I was proud.”

Wanting to relay those experiences to his siblings, Zhamirr wants to bring his knowledge of farming into his home.

“My older brother is someone that I want to teach it to,” he said. “He has seizures, so I want to tell him how to garden and eat his vegetables. I think that will help him mentally. My little sister, too. She is a pre-diabetic, so she needs to eat vegetables.”

Not only is the farm promoting a healthier community through self-sustainability, it’s also giving youth a productive outlet to keep them safe.

Outside school, Zhamirr said he watched his peers succumb to dealing drugs to make money during their spare time.

“It kept me out of trouble during the summer,” he said. “I watched my friends get locked up while I was out here doing good stuff.”

One West Side student who worked on the farm, Azzariah Edwards, said his time was better served at the school as well.

“It kept me off the streets,” Azzariah said.

Growing Business Opportunities

Part of keeping students at school through the urban farm fulfilled Cook’s vision of bringing the project to West Side.

Through the school’s “West Side Ave” business program, Cook wanted his students to find ways to turn their ideas into profit, utilizing the urban farm as an entrepreneurship opportunity to become self-sustainable.

Using the herbs and produce grown on the urban farm, students developed an artisan hot sauce called “Rider Heat” after the school’s sports teams, offering three different flavors.

“These are some of my brightest kids, but they’re also some of the hustlers we have in this building,” the principal said. “In schools all around the world, kids are reluctant to try new things because they’re afraid to fail. It’s going to take those brave students that are going to venture into something like this.”

Through the West Side Ave website, students can earn a residual income from each hot sauce sale. Each student makes a testimonial video about how they plan to use the money, and buyers have the option to direct a portion of their payment toward a particular student.

By earning a residual income through the hot sauce sales, Cook said the goal of the project is to keep students at the school to fulfill their education as opposed to missing class, or even dropping out of school, to work side jobs.

The school club also provides students an opportunity to showcase their creativity while gaining exposure to business and entrepreneurial experiences outside the classroom.

“It’s rare that a kid that drops out because they just can’t hack it. Usually what gets kids is the financials,” he said. “Either they’re going to go outside making money illegally, or they’re going to work these odd jobs… It’s about how can I show kids to get this money.”

This story was co-produced in collaboration with CivicStory and the NJ Sustainability Reporting project.