ATLANTIC CITY — From Virginia to Los Angeles, they came to their concern over the environment and sustainability from different places but all arrived at the same conclusion.

Entrepreneur Wes Gober, attorney Arielle King and the NAACP’s senior vice president Jamal Watkins arrived at one of those places, the NAACP national convention, to urge young people to take up the mantle of environmental and climate justice leadership.

Panelists at the NAACP national convention’s Roy Wilkins Luncheon on Monday, July 18, 2022. Photo credit: AC JosepH Media

Marcus Sibley, the National Wildlife Federation director of conservation partnerships for New York, New Jersey and Connecticut, led a conversation among those leaders at the convention’s prestigious Roy Wilkins Luncheon on Monday (July 18), putting environmental concerns at the center of the convention.

While the NAACP is best known for its fight for civil rights for African Americans around the country, Sibley, the New Jersey State NAACP environmental justice chair, said the environment is also a front in that battle and hoped the luncheon would be a call to arms for young people of color becoming more connected with it.

He asked everyone in the audience to attend at least two city council meetings before the end of the year because it is at the local level where those decisions take place.

Roy Wilkins Luncheon moderator Marcus Sibley. Photo credit: AC JosepH Media

Sibley, the president of the Southern Burlington Branch of the NAACP, said whenever the environment and sustainability are discussed, “there needs to be an NAACP representative at that table. How long are we going to continue to let people who don’t care about us speak for us? The way we fight [against] social injustice, we need to fight climate change and [advocate for] the environment in the exact same way.”

Gober, the founder of the Black Oak Collective, said he was surrounded by mentors who enlightened him about the need to bring Blacks and other minorities together over the environment. The Black Oak Collective brings together African American professionals, students and organizations from the District of Columbia, Maryland and Virginia with respect to environmental issues.

“[We come together] for mentorship, to build skills and share career opportunities,” Gober said. “[Working with mentors], I gained a lot of the policy literacy and communication skills. I was placed in proximity with a lot of great mentors, climate justice mentors, who taught me a lot of what I know.”

Gober said the current COVID-19 pandemic has driven home not only racial healthcare disparities but the impact environmental injustice has on communities of color.

“People are dying from our fossil fuel corporations and polluting companies exploiting our communities right now,” Gober said. He suggested that while media attributes high rates of diabetes, asthma and heart disease in the Black community to genetics or culture, the real culprit is often environmental pollution and the effects of climate change.

Wes Gober. Photo credit: AC JosepH Media

Corporations, Gober said, “are planning on a future that continues to exploit Black communities. We can build [environmentally safe] communities that center on young people, that give young people good union jobs and good paying jobs, and make all of our communities better, more walkable, better places to live.”

King, a staff attorney for the Environmental Law Institute, said her neighborhood growing up faced a bombardment of environmental hazards from pollution.

“I grew up in a place where there were a lot of different sources of pollution that were impacting my neighbors and my friends,” King said. “Almost everybody I grew up with had a different type of asthma.

“There was limited access to green space and there were literally trains that were…holding crude oil that were less than two feet away from a housing project like in my neighborhood. This was literally killing people.”

She said those experiences led her to pursue a legal career in environmental justice with a concentration in political ecology. She did her senior thesis on the lead pipe water crisis in Flint, Michigan.

She said, though, that she was disappointed while attending one of the top environmental law schools in the country on how little it focused on environmental justice, so she started a student group while in school.

Arielle King. Photo credit: AC JosepH Media

Watkins, senior vice president of strategy and advancement with the NAACP, grew up in Los Angeles with its legendary “smog” sparked by pollution from automobiles.

“As a kid, you would realize through the news that sometimes we would have good air quality days and then you would have bad air quality days,” Watkins said. “On bad days we couldn’t go outside. I’m a kid and I wanted to go outside and play and I didn’t understand.”

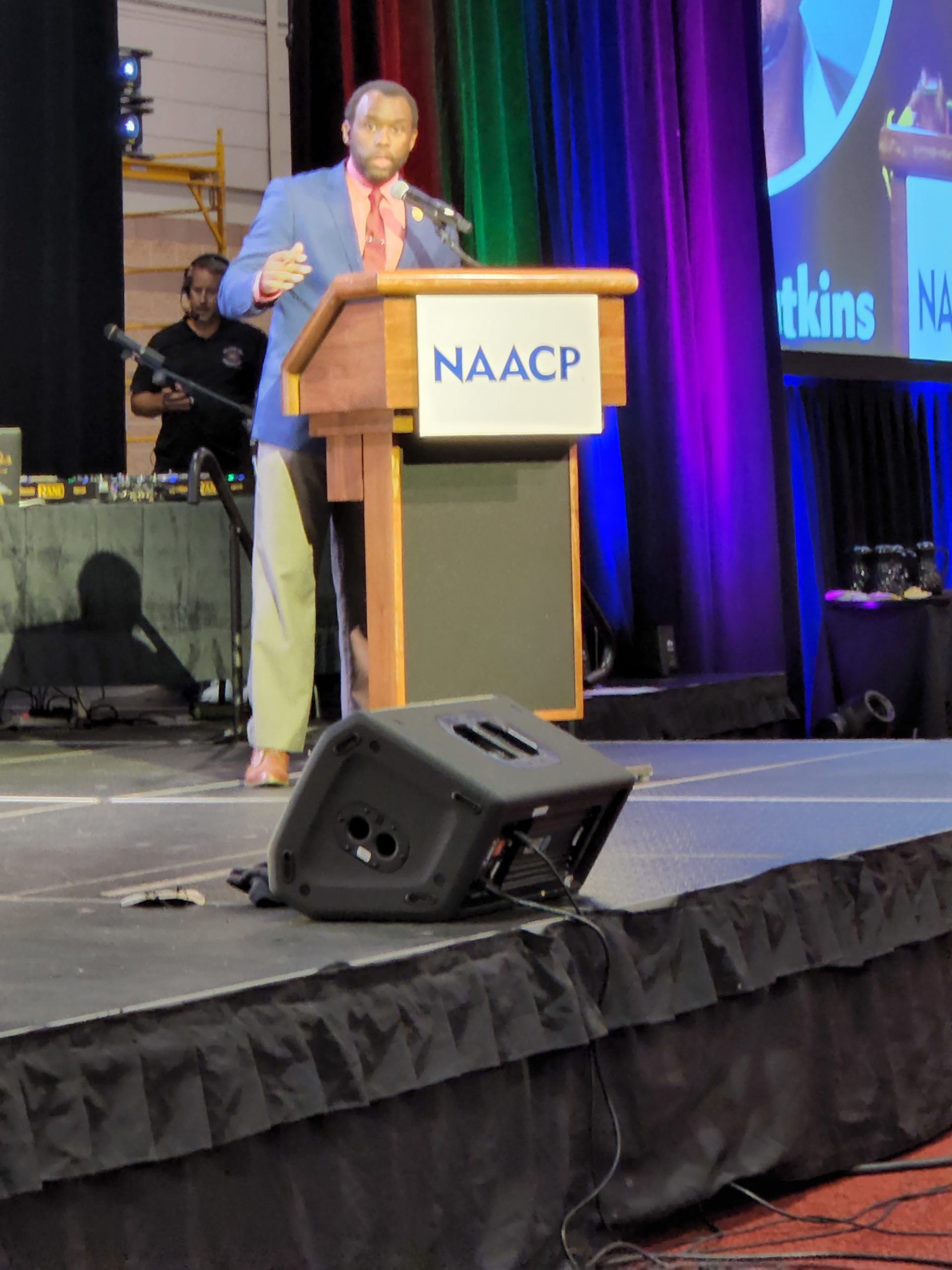

Jamal Watkins. Photo credit: AC JosepH Media

Watkins said has he learned more about air pollution, and when his friends talked about having issues of asthma, he started to connect the dots.

“I began to think about the connectivity of the world and decided that there has to be something that we can do collectively to make a difference,” Watkins said.

He urged young people to “secure the bag,” because there is a financial incentive for corporations to keep polluting and failing to clean up the environment, and they must turn those economic arguments around to make headway with decision makers.

Sibley said the NAACP is in a unique position to have Blacks speak in one voice on environmental justice and sustainability. He challenged the young people in the audience to not only keep the conversation going, but also to confront their local leaders about making a difference at the grassroots level.

This story was co-produced in collaboration with CivicStory (www.civicstory.org) and the NJ Sustainability Reporting Project (www.SRhub.org). It was edited by Denise Clay-Murray, a veteran Philadelphia-based independent journalist, longtime member of the National Association of Black Journalists and a regular contributor to the Philadelphia Sunday Sun among other print and digital publications.