After installing solar panels, Old Bergen Church in Jersey City saves at least $10,000 in utility costs and earns about $8,000 yearly via SREC credits. (Source: Pastor Jon M. Brown)

By Nicola A. Menzie| Managing Editor, Faithfully Magazine

This story was produced in collaboration with CivicStory and the NJ Sustainability Reporting project.

(NEWARK, N.J.) — Clean energy sources like solar and wind can be good news for the environment and for overburdened communities — which tend to be predominantly Black and Hispanic, low-income, and exposed to higher pollution levels. But in addition to being a boon for the environment and marginalized communities, clean energy can significantly impact a church’s finances.

On average, the biggest part of a church’s budget goes toward payroll, with another large chunk going toward building expenses, such as a mortgage and physical maintenance. But a major part of a church’s finances covers electricity and heating costs, which could be significantly reduced by using a renewable energy source, such as solar.

“I would say the number one trend that I find for every organization is the utility bill,” Rodney Haveman, a local pastor, told Faithfully Magazine. “The energy bills that are almost completely fossil fuel [are] the most expensive portion of a congregation’s budget that doesn’t have to do with staff.”

Haveman, also a community organizer, knows first-hand the difference solar can make for a church.

Crunching the Numbers

Parkside Community Church, where Pastor Haveman has served for 20 years, installed solar arrays on the roofs of its two buildings in 2017.

Located in Westwood, the Reformed Church of America (RCA) congregation pays about $14,000 annually for utility services to its worship building and pastor’s parsonage. That is $2,000-$3,000 less than it used to spend annually before transitioning to solar.

According to Haveman, the biggest difference has come from the state’s Solar Renewable Energy Certificate (SREC) program, which provides a credit when a facility’s solar photovoltaic (PV) system generates 1,000 kWh of electricity. Residents and businesses that receive SREC credits can then sell them to utility companies. The monthly market price for a single SREC credit tends to fluctuate, though the rate has stayed well above $200 for the past 12 months.

“We’ve been able to earn somewhere around $7,000 each year for the last six and a half years,” Haveman said of his church’s participation in the SREC program, one of several incentive and rebate options available to those who adopt solar.

The 50-member church has seen a combined savings and income of upwards of $10,000 yearly from its transition to a clean energy source.

“I think that’s a pretty conservative estimate for what solar power has meant for our congregation,” he said.

The next step toward greater efficiency involves replacing the church’s current lighting with LED lights, which Haveman hopes will further decrease their energy consumption and utility bill.

In the meantime, he continues his work as a community organizer with New Jersey Together — a multi-faith, nonpartisan coalition — to help religious congregations take similar steps to not only save money and potentially make money but also contribute to the state’s goal of using 100% clean energy by 2035.

New Jersey Together, with chapters in Jersey City, Morristown, and Essex County, empowers religious congregations and nonprofit organizations to lobby for issues relevant to their respective communities. The broad-based coalition was founded in 2016 and is affiliated with the Industrial Areas Foundation (IAF), a national network of faith- and community-based organizations established in 1940.

Known primarily for organizing communities to take action on criminal justice, education, and housing reforms, New Jersey Together launched a Green Energy Initiative in January to help congregations go green and potentially reap rewards from state and federal incentive programs.

The average 4 kW solar PV system costs about $12,040 in New Jersey, according to EnergySage, which connects consumers with vetted installers and providers. However, state and federal rebates and grants for nonprofit organizations can drastically reduce costs associated with installing solar panels.

Positioned as an owner’s consultant, New Jersey Together helps congregations “navigate the system and take advantage of all the incentives that are available,” Haveman said.

While the assistance is free for members, Haveman also works with various outside congregations.

In addition to holding discussions with the Jewish Federation of Northern New Jersey to explore partnering on various “energy initiative work,” he has engaged with his own RCA denomination to assist other local congregations. The pastor and community organizer is in similar talks with the Presbytery of the Northeast of New Jersey, which has 102 congregations, and the Meadowlands district of the United Methodists of New Jersey, which has 85 congregations.

Among New Jersey Together’s members, Haveman estimated that about 50 congregations across its three chapters are pursuing solar or other forms of clean energy and efficiency.

Pastor Javon Allen of Peace Temple Church of God in Christ in Newark. (Sources: Google Street View 2021; Courtesy of Javon Allen)

One of those churches is Peace Temple Church of God in Christ (COGIC) in Newark, led by the Rev. Javon Allen, a longtime member of Jersey City Together who also participates in Essex Together.

“They’ve already looked at our building, and we are a good candidate for the solar panels,” Allen told FM, describing an initial walkthrough of the church. “They inquired about the LED lights [and] they inquired about the HVAC system.”

The Pentecostal pastor is also considering upgrading insulation for the brick-and-concrete church, built in the 1950s.

“It’s a commercial building, and we still have the commercial windows on the front of our building. So we need better [energy] efficient windows because … in the winter our heat is going outside and in summer our heat is staying inside,” he said.

Having already undergone a review of its energy bill, next up for Peace Temple COGIC is a closer survey of its building and facilities during a scheduled July vendor visit.

The church, which currently has about 20 members, has paid as much as $3,500 per month on its utility bill in previous years. Although much lower nowadays, Allen implied that a $600 utility bill was still too high.

Eager to continue on the path to electrification, Allen believes his church could see “tremendous savings” from installing a solar array. He pointed to Haveman’s church, about 30 minutes away in Westwood, as an example of the kind of impact clean energy could have on overhead.

More Than About Money

The benefits of solar are more than about dollars and cents.

Newark, New Jersey. (Source: Unsplash/ Emmanuel Ogbonnaya)

Jennifer Souder, a LEED expert who works for the Center For Urban Policy Research at Rutgers University, emphasized the environmental significance of churches reducing their reliance on fossil fuels.

“A lot of communities, especially overburdened communities in New Jersey, are the recipients of the worst of the greenhouse gas emissions. So by transitioning to cleaner energy, it is impacting the community by reducing pollution in the air,” Souder said.

Studies have shown that Black and Hispanic people are disproportionately exposed to air pollution and its health harms, although they are less likely to contribute to the nation’s poor air quality. In New Jersey, home to the most Superfund sites (115 ) in the country, residents contend with pollution from highways, a major airport, and power plants. According to the American Lung Association, residents in Essex County, New Jersey’s largest and most diverse county, have some of the highest cases of asthma and lung diseases in the state.

“I think sometimes it’s hard for people to make the link between the larger scale of pollution and then [the impact of retrofitting] one building. But when you start doing it on a larger scale in a community, you can really impact the environment,” said Souder, who also worked on the official New Jersey Green Building Manual.

More than 4 million solar energy systems have been installed nationwide, according to the Solar Energy Industries Association (SEIA), the national trade association for the U.S. solar industry.

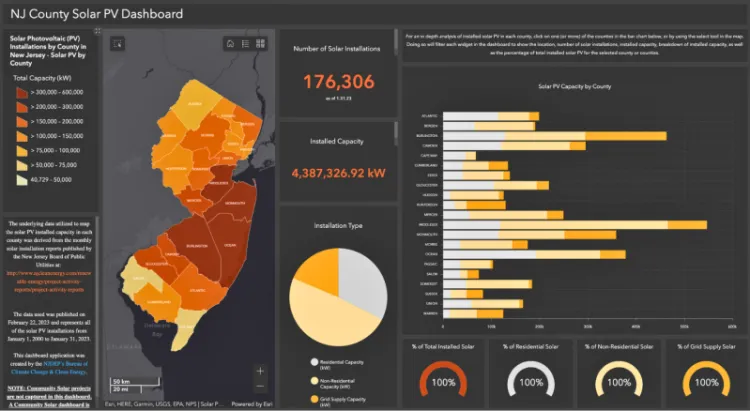

The SEIA ranks New Jersey as the eighth-largest producer of solar energy. According to the New Jersey Board of Public Utilities May solar activity report, the state has more than 178,000 solar PV systems with enough capacity to power 423,000 homes for a year (about 4.5 million kW). Less than 0.5% (827) of the state’s installations occurred at churches and other nonprofits.

New Jersey County Solar PV Dashboard is based on data collected through January 31, 2023. (Source: NJDEP)

Solar PV systems were installed at about 2,509 houses of worship nationwide (1.9% of all houses of worship) through 2021, based on an analysis funded by the U.S. Department of Energy. The report also concluded that solar PV systems “are disproportionately located in relatively wealthy, White, and educated census tracts, compared to the overall population.”

Newark, where the Rev. Allen’s Peace Temple COGIC congregation is located, is New Jersey’s most populous city and one of its poorest. The city’s 305,000-plus residents are also predominantly Black and Hispanic or Latino. The only local religious institution currently listed as having a solar array on site is the Catholic Church’s Archdiocese of Newark.

The state’s emerging community solar program, intended as an alternative for residents who rent, cannot afford to install solar panels, or are otherwise locked out of setting up a solar PV system, is also limited. Just one local site currently exists (with another under construction) for Newark residents wanting to participate in community solar, which has 25 active and 101 planned sites statewide.

Haveman, the pastor and community organizer, said New Jersey Together prioritizes marginalized communities in its green energy push for congregations.

“The last folks that get some of the aid and initiatives and incentives for transitioning to green energy or renewable energy are low- and moderate-income communities, often minority communities,” he told FM.

Jennifer Souder is a LEED expert who works for Rutgers University’s Center For Urban Policy Research. (Source: Courtesy of Jennifer Souder)

Following Through

The timeline for a solar installation project varies, partly due to the unique needs of a congregation. However, moving from an initial consultation or audit to having a solar PV system up and running can take as little as a few months — assuming there are no major challenges or natural disasters.

About six months into New Jersey Together’s Green Energy Initiative, none of the member congregations that expressed interest in exploring solar have had panels installed.

“At this point, most of our congregations are in at least some area of where Rev. Allen’s church is in,” Haveman said.

For Haveman, one obstacle has been finding a dedicated coordinator with the “time and energy” to fully commit to their congregation’s solar project.

“Many of our congregations are working so hard in their ministry, doing so many of the good things that churches do, that getting any one leader in that organization to step up … and see the vision through can be difficult,” Haveman admitted.

The biggest challenge so far, he said, involves New Jersey Together’s process of building leadership teams to take ownership of the initiative among its various chapters.

“We’ve been doing criminal justice for quite some time. We’ve been doing education reform for quite some time. And in both of those areas, we have a lot of really great wins that we’re very proud of,” Haveman said. “But this energy initiative … is very new for us.”

Despite the challenges, Haveman encourages congregations to pursue energy efficiency however they can.

“I can say without hesitation that it’s not impossible. For any congregation in New Jersey, it’s not impossible,” he said, addressing potentially wary leaders.

“Any step you make is helpful for your congregation, for your community, and to fight climate change. All three of those are worth your time and energy to make the world a better place,” Haveman said.

Souder, the LEED expert from the Center for Urban Policy Research at Rutgers, expressed a similar view.

“Houses of worship are a big opportunity to push the envelope or to demonstrate some of the things that can be done,” she said. “[They] can help build trust within especially overburdened communities that are sometimes missing out on the transition [to clean energy]. So I think churches, in particular, are an important place to focus.”

This story was produced in collaboration with CivicStory as part of the New Jersey Sustainability Reporting project. Find more stories like this at the New Jersey Sustainability Reporting Hub.