Delaware Bay in Cape May

By Myara Gomez | The Signal

This story was produced in collaboration with The Signal (TCNJ) and CivicStory as part of the Ecology-Justice Reporting Fellowship.

Shoreline erosion has become a serious concern in New Jersey, as the coastline erodes due to sea level rise, strong wave action, and coastal flooding. The constant movement of water carries away the sediment from the shore, causing the coast to slowly disappear. The Delaware Bay (Salem, Cumberland, and Cape May counties) is specifically impacted, leading to an increased effort across the state to protect the coast.

The Delaware Bay is unique in several ways—but most importantly, it is a home for wildlife. The bay has the largest population of horseshoe crabs in the world and the second-highest concentration of shorebirds in North America. But the region, teeming with life and biological resources, is at risk of changing.

“The tide moves in, it moves out, it takes sand away, it chews away at marsh edges—that is just part of the dynamic system of the coast,” said Shane Godshall, Habitat Restoration Project Manager of the American Littoral Society.

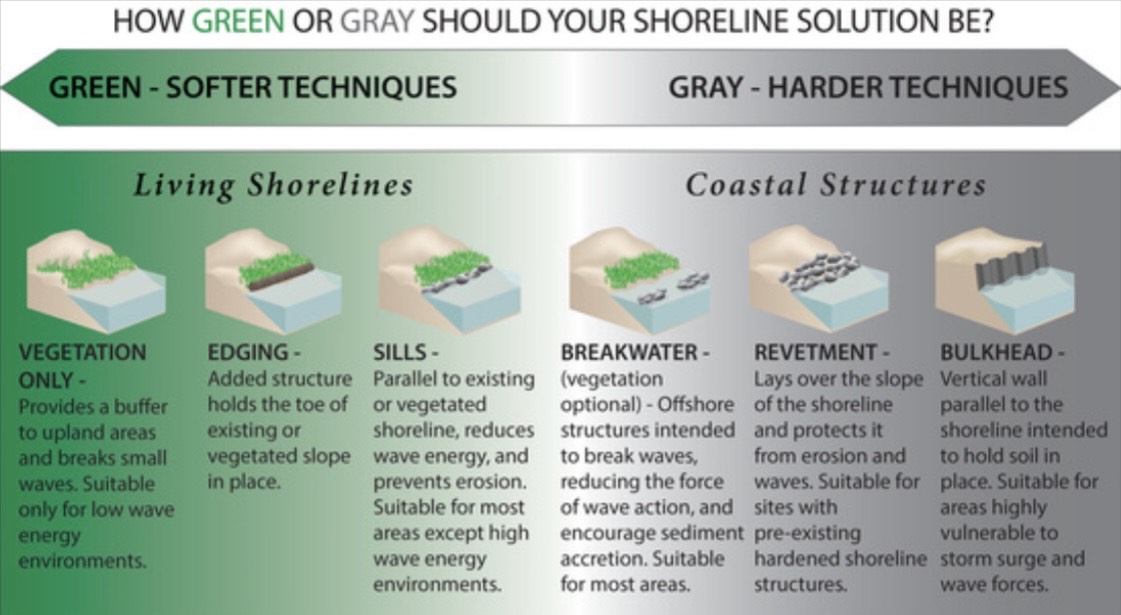

As a solution, the American Littoral Society has been implementing living shorelines all across the bay. Some of the beaches are Dyer’s Cove, Reeds Beach, Cooks Beach, and Kimbles Beach. Living shorelines are made out of natural materials—like plants, sand, or rock—that help stabilize the coast by connecting land and water while still allowing the ecosystem to function as normal. Living shorelines can absorb wave energy, improve water quality, and store carbon.

“We have also implemented a project which restored marsh habitat at Thompson’s Beach and a large-scale project in the Maurice River intended to protect marsh from erosion,” said Godshall.

Prior to implementing a living shoreline, the surrounding area needs to first be assessed to uncover the smartest solution to erosion. Some areas require different solutions. The first step is site analysis, where an evaluation is made based on wave energy, elevation, wind, soil type, and vegetation. The next steps are permit approval, site preparation, installation, and monitoring.

Photo: fisheries.noaa.gov

“Living shorelines are great in some places but they’re not as effective in others. So, if we have a project in Fortescue, the erosion is very heavy but there’s a lot of fetch, there’s a lot of big waves that come through so you need something offshore that’ll break those waves up,” said Godshall.

Godshall mentioned that the American Littoral Society also installed breakwaters in Fortescue. A breakwater is an off-shore structure built to protect an area from strong waves. They do this by intercepting the waves before they reach the coast. While it may sound similar to a sea wall, the two are quite different: sea walls run directly parallel to the shoreline, while a breakwater is built offshore to alter or disrupt wave patterns. Often, they are as straightforward as a large pile of rocks off the coast.

Efforts to support a healthy ecosystem extend beyond coastal rehabilitation. The Littoral Society is also managing a marsh restoration project in Cumberland County’s Maurice River, focusing on increasing carbon sequestration. Carbon sequestration is the process of capturing and storing carbon dioxide, often produced by decaying organic matter, so as to lower its effect on our atmosphere—something marshes are quite adept at doing via plant tissue. Without this process, the atmosphere warms. The project in Maurice River uses coconut fiber logs and semi-permeable barriers to minimize the strength of the waves and allow marshes to thrive.

How are these projects funded? Most of them are federal or nation-wide funding opportunities, with a majority of projects funded through the National Fish and Wildlife Foundation. These funds are especially necessary for the communities surrounding the Delaware Bay, many of which do not have financial means to contribute to these projects. Cumberland County is New Jersey’s poorest county. Though PBS puts the county’s poverty rate at nearly 20%, it does not receive as much funding as other counties do. Godshall believes it is because of the difference in ratables, or items and assets that can be appraised or estimated, like property.

“On the Atlantic coast, you have a lot of ratables—a lot more money that comes in from the tax base and where they can afford to pony up some funds to do some of these projects. But that’s generally not the case in the bayshore,” said Godshall.

As towns along the Atlantic coast have more money and property, they are able to use tax dollars to fund their projects. But just because Delaware Bay communities don’t follow the same model doesn’t mean they aren’t invested in the shore. Godshall explained that when the American Littoral Society makes calls for volunteers, community members consistently assist with building shell bag reefs and other similar tasks.

These shell bags, a method of oyster reef construction, bring several benefits, including protecting the shoreline, providing habitats for marine life, increasing the oyster population, and cleaning the bay. In fact, the oysters themselves clean the water; “One adult oyster can clean up to 50 gallons of water per day,” per the American Littoral Society.

As part of their efforts, the American Littoral Society makes sure to speak with mayors, city councils, and whomever else they can. They strive to be as collaborative as possible so these projects can become a reality.

“The municipalities themselves are usually very good—they’re happy to see us show up, and they are happy to participate and help us move our projects forward however they can,” said Godshall.

The Delaware Bay is still facing significant challenges around its coastline. As every means to improve its health is explored, it is crucial that surrounding communities and organizations continue to collaborate and invest in these projects—securing a sustainable future for the bay and its surrounding communities.

Myara Gomez is a junior at The College of New Jersey. She is a staff writer for The Signal (TCNJ) and a CivicStory Reporting Fellow. This story was produced in collaboration with The Signal and CivicStory as part of the Ecology-Justice Reporting Fellowship.