This story appeared on page one of The Press of Atlantic City on August 31, 2020.

“This is really going to put Salem on the map for green energy,” said Jennifer Jones.

Standing on the steps of the county courthouse, Jones, executive director of the Salem County Chamber of Commerce, is enthusiastically contemplating the impact of Gov. Phil Murphy’s New Jersey Wind Port project.

Ever since Murphy announced the plans for the project in June, calling it a “once-in-a-generation opportunity,” the Wind Port, billed as the first in the nation to be built specifically to support the development of offshore wind farms, has been generating buzz in the region.

For state officials, it’s part of the governor’s goal for New Jersey to reach 100% clean energy by 2035.

But for residents in this historic, rural county, the project offers something else, jobs — 1,500 good-paying green energy jobs, generating a $500 million bump in the economy, all beginning by 2021.

This will be the largest economic development project in the past 50 years, Jones said.

“This will be a boom for everyone. It’s an opportunity, once in a lifetime” according to Charles Hassler, a freeholder in Salem County, where the project will be located. “We have the opportunity to be the leaders in the country in energy. This is a big deal.”

Salem County is the smallest county in the state in terms of population, with much of its 372 square miles still used for farming. The county has the largest amount of preserved farmland in the state, with 40,234 acres — one out of every six acres. Some of the farmland is being set aside for alternative energy production.

A solar field that will be the largest in the state is planned to cover 800 acres in Pilesgrove Township, at the Nichomus Run Solar Farm, according to developer Dakota Power Partners.

Jones says the combination of green energy projects, jobs and the county’s available land is a good fit.

“To have a project that is going to change the footprint of our economy while still being good for the environment is a great thing,” she said of the wind port. “It’s going to be a great fit for us.”

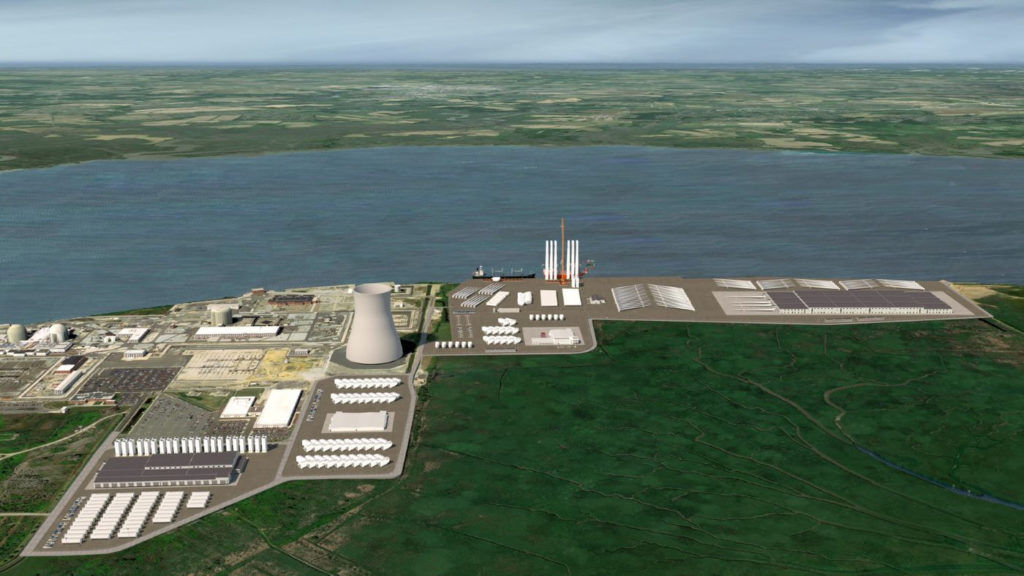

The site of the proposed wind port is a 10-mile boat ride from Billy’s Boat Works, near the Port of Salem. Huge barges cruise the Delaware River on their way to and from ports like Philadelphia and Wilmington until the giant cooling tower of Artificial Island comes into view on the horizon. The planned site sits quietly undeveloped next to the cooling tower on the banks of the river among acres of swaying cattails.

Site next to nuclear plants

The wind port site is part of Artificial Island, a man-made island home to three nuclear power plants, owned by Public Service Enterprise Group (PSEG), a partner with the state on the project.

Salem Nuclear Plant went on line commercially in 1977, and was later joined by Hope Creek Nuclear Generating Station in 1986. With its combined output of 3,572 megawatts, the Salem-Hope Creek complex is the largest nuclear generating facility in the Eastern United States and the second largest nationwide.

The project will include both a manufacturing site on 200 acres along the Delaware River, in Lower Alloways Creek, where parts for wind turbines would be built, and a marshaling and staging area where the turbines would be assembled and put on ships, to be delivered to wind farms along the Eastern Seaboard.

The wind port site was chosen because of its quick access to the ocean with no bridges or other obstacles that would obstruct the transportation of the turbines that will be “as tall as the Eiffel Tower,” according to Tim Sullivan, CEO of the New Jersey Economic Development Authority.

The combination of a green energy facility and a nuclear plant sharing marshy Artificial Island may seem incongruous. But both are considered sustainable energy sources, according to James Conca who writes about energy in Forbes magazine.

A bigger factor is cost. While the cost of most other forms of energy has gone down (wind is a quarter of the cost of nuclear power), nuclear power is four to eight times higher than it was four decades ago, according to Project Drawdown, which researches and analyzes climate solutions. And, of course, there’s the risk and safety concerns of nuclear power from accidents like what occurred at Three Mile Island and Chernobyl, to disposing of the spent fuel rods.

Salem getting ready

Freeholder Hassler remembers when the nuclear plant was built and some of the qualified, skilled jobs that went to workers outside the region.

“We’re going to beat that this time,” he said. “We are going to find out what we need out there to get our workforce ready.”

The local community college and vocational-technical career school are in the planning stages, in conjunction with the chamber of commerce, to develop programs to prepare the local workforce for the opportunities that will be available at the wind port, added Jones. And workers that land jobs but who live outside the community will still be adding to the local economy, the local businesses and the housing market, she said.

“The outpouring of support from our residents was terrific,” she said. “They’re not only excited about it being green energy, but because of the high-paying manufacturing jobs that this is going to bring to our area.”

Hassler agrees that the county is poised to deliver what is needed for the wind facility to work, from a railroad that runs to the Port of Salem, housing, business space and an airport.

In Salem City, he said, where the workforce is predominantly blue collar, the jobs and economic spinoff will be welcome.

Several empty storefronts line Broadway, the main street through Salem. About 26% of families and 28% of the city’s population live below the poverty line, according to census information.

“We can use the employment,” Hassler said. “This is a glass factory town that doesn’t have any more glass factories.”

But he, along with others, are cautious until he sees real action take place. Hopefully, he said, Murphy will come through with the plan, estimated at between $300-400 million, which the New Jersey Economic Development Authority is hoping to finance through a combination of public, private and mixed public-private sources.

“The buzz in the town itself is hopeful,” said Kim Lounsbury, a sales associate at Parker Jewelers, a longtime business located off Broadway in the center of Salem. Lounsbury believes it will create jobs, boost the housing market, and benefit small businesses like Parker.

“We’ll be fixing all their watches so they can get to work on time,” she said. “It’s encouraging that PSE&G, as a competing industry, is also on board and thinking that it has sustainability and a future.”

This story was produced in collaboration with CivicStory and the New Jersey Sustainability Reporting Hub project. It was originally reported by Vernon Ogrodnek for the Press of Atlantic City, and may be re-distributed through the Creative Commons License, with attribution.