New Jersey resident Nina Persson Reed supports the survival of endangered monarch butterflies by nurturing them from eggs to butterflies.

In July 2022, the migrating monarch butterfly (Danaus plexippus plexippus) was added to the International Union for the Conservation of Nature’s Red List of endangered species.

Although monarch butterflies are found in North America, people all over the world are expressing their sadness and concern for the possible loss of the species, including New Jersey resident Nina Persson Reed.

A self-educated advocate for environmental sustainability, she has always had an interest in nature and gardening.

“I have always found it very soothing to be in nature. It’s one of those disconnected places you go to take a deep breath,” she said, “It is something as simple as bringing a few flowers into the yard and suddenly you have life. It’s like a therapy and it’s a way to bond with something very comforting.”

The garden

Reed focuses her gardening specifically on providing a natural habitat for native New Jersey species. She has educated herself about the state’s native plants and animals and focuses on adding only native plants into her garden.

“I try to focus a lot on the natural flora of New Jersey. I’m not looking to plant something that doesn’t belong here,” she said.

Her garden is mostly made up of plants that serve pollinators, such as common milkweed, a native plant that is the sole food source for monarch caterpillars.

Reed holds two certificates: one from Monarch Watch that certifies her property as a monarch waystation; and the other from the National Wildlife Federation that declares her property a certified wildlife habitat. To obtain these certifications, properties must have a variety of native pollinator plants, milkweed, shelter, and a water source.

Raising monarch butterflies

After Persson Reed’s monarch butterfly eggs hatch, she keeps the caterpillars in mesh cages. Photo credit: Nina Persson Reed

After moving to the US from Sweden when she was 19 years old, Reed became very interested in the life of monarch butterflies and has been raising them for the past 15 years.

Almost daily, she will check her milkweed for eggs. When she finds eggs she brings them inside and rinses them with a diluted mixture of water and bleach, then rinses them with plain water in order to minimize the risk of ophroyocytis elektroscirrha, a virus that is unique to monarchs. She then places the leaf with the eggs in a small container until they are born.

After being born the caterpillars are kept in mesh cages, separated by size to prevent predation of the smaller caterpillars. Each cage is cleaned daily and fresh, clean milkweed in floral tubes is added to the cages. Any caterpillar that looks sick or is behaving abnormally is separated into a cage by itself.

When the caterpillar is ready to go into a chrysalis, it climbs to the top of the cage. When the chrysalis is hardened, it is placed into a separate cage for about 10 to 14 days until a butterfly is born. The butterfly is checked for disease and then released back out into the yard where the eggs were found.

This whole process takes approximately four weeks.

When the caterpillar is ready to go into a chrysalis, it climbs to the top of the cage. When the chrysalis is hardened, Persson Reed places it into a separate cage for about 10 to 14 days until a butterfly is born. Photo credit: Nina Persson Reed

Reed also reports sightings such as first milkweed sprouts, first butterfly, first egg, etc. to Journey North, an organization that creates maps that show the species’ activity across the country.

A species on the verge of extinction

IUCN estimates the endangered migrating monarch butterfly to have suffered a population decline of 22% to 72% (depending on the method of measurement) since the 1990s. Both the eastern and western populations reflect this trend.

Over the years, the number of Reed’s releases has declined rapidly. “Ten years ago, I would release probably 300 to 400 throughout the season. Last year I was down to about 80 and this year I currently have about eight caterpillars,” she said.

In past years, Reed would refrain from touching any caterpillars until about August when the fourth migrating generation arrived, with the latest release being in late September. However, with the sharp population decline, she is taking in any that she has been able to find to ensure their survival.

“Since the numbers have been so incredibly low, I have taken in the ones that I have been able to find. It is only a handful when technically there should be hundreds,” she said.

This population decline is heavily due to logging, deforestation, and urban development, which have all contributed to habitat loss. The usage of pesticides and herbicides has also played a part in the population decline, as those substances kill butterflies (and other pollinators) and milkweed, which is necessary for monarch caterpillar survival. Habitat loss and pesticides all across the country are impacting the survival of this migrating species, which goes through four generations as the butterflies make their journey between Mexico and Canada.

“They need to be able to make their journey from Mexico, across the country, and back again,” said Reed, “They need milkweed for the caterpillars to survive, and nectar flowers for the adult butterflies to fuel up and keep flying. We have gotten so out of hand with eliminating anything creepy crawly. Also, a lot of natural habitats have been leveled so there is nowhere to lay eggs or get food.”

Climate change has also started to impact monarch butterflies. Drought and excessive wildfires are killing off milkweed. Extreme temperatures have altered monarch migration patterns, compelling them to move early and arrive somewhere before the milkweed has had a chance to grow.

The future of this species is unknown, but it is looking to be very bleak.

During their migration, monarch butterflies make their way through New Jersey between September and November. They spend some time in the south Jersey area, eventually making their way to Cape May to cross the Delaware Bay. Usually, thousands of butterflies can be seen in Cape May in the fall, but in recent years this number has dwindled.

“We’re not talking 20 to 30 years, it could be closer to five or ten,” said Reed about the timeframe in which monarchs may be extinct. “They just can’t sustain, they have to have what they need and [their habitat] is disappearing much, much too quickly.”

Get involved to help monarch butterflies

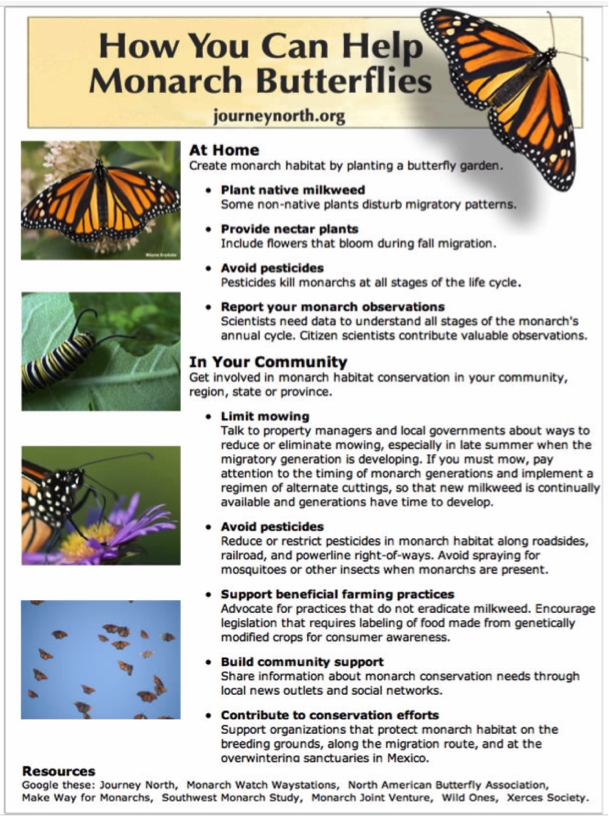

If you are interested in helping monarch butterflies, there are several things that you can do.

If you have a garden, try to focus on planting only native plants and plants that cater to pollinators. Try to shy away from herbicides and pesticides. Paying more attention to your garden or yard and the actions that you take during upkeep are very important for the future of monarch butterflies.

“Search for native plants of New Jersey. Proceed with caution with anything that doesn’t normally belong as far as weed killers, mosquito spraying, and backyard foggers. Just give it a little bit of thought and do your research,” said Reed.

You can report sightings to Journey North to contribute to data collection and population tracking. South Jersey residents can report sightings to the South Jersey Butterfly Project, which covers eight counties including Atlantic, Camden, Cape May, Ocean, Burlington, Salem, and Cumberland. North Jersey residents can report sightings to the North Jersey Butterfly Project, which covers the remaining thirteen counties.

You can also look into organizations in your area that focus on monarch butterfly research and education such as the New Jersey Audubon’s Monarch Monitoring Project. This research project focuses on monarch butterflies migrating along the east coast. The organization gathers data on monarchs that move through Cape May. Volunteers and MMP staff conduct informational programs on tagging and monarch biology. You can support this project by adopting a monarch at this link.

You can also look for local pollinator gardens, educational programs, or garden clubs near your area to learn more and get ideas for involvement. One example is the Garden Club of New Jersey, which has clubs in all but four NJ counties. Click here to see clubs near you!

Finally, above all else, it is so important to educate yourself. Learn what is around you, what is native to where you live, and simple things that you can do to help.

“It is very disheartening when people post a request for a good company to spray their yard for mosquitos and then the next second ask where they can buy local honey to help allergies. You can’t have it both ways,” said Reed.

Expressing her love for monarch butterflies and the work that she does, Reed said, “It is an awe-inspiring transformation to watch. They grow 300% in size over two weeks. It’s this little teeny tiny egg. It doesn’t look like much of anything, and then the caterpillar goes into its chrysalis and then comes out as a butterfly, and it’s just very heartwarming. Every butterfly that is born, I can’t believe it: There it is.”

Credit: Journey North

This story was produced in collaboration with CivicStory (www.civicstory.org) and the NJ Sustainability Reporting project (www.SRhub.org).