Could eating an oyster be a way to save the planet?

Maybe not on a large scale, but it is one way people can take a bite out of New Jersey’s sustainability issues.

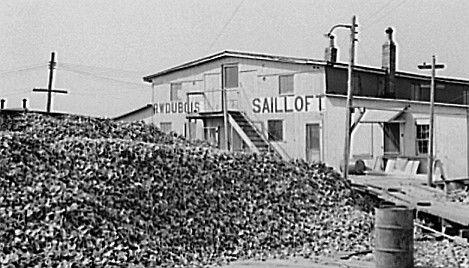

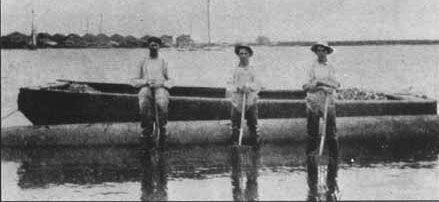

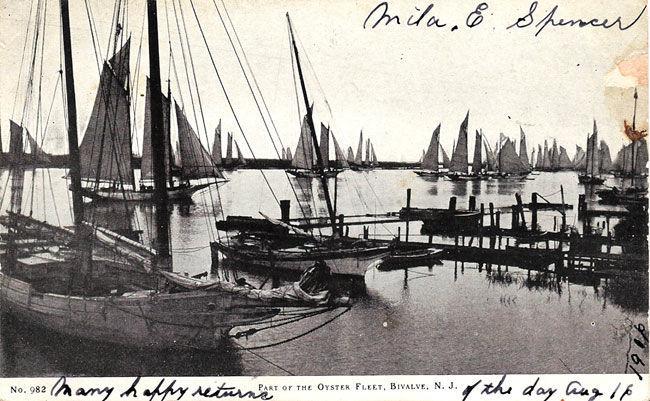

Oyster farming in New Jersey was once a booming industry bringing in millions of bushels a year beginning in the 1800s. But in the 1950s, the oyster industry took a major hit after a virus wiped out a large portion of the oysters in the Delaware Bay.

Fortunately, things are looking up for oysters.

At the Rutgers University Haskins Shellfish Research laboratory in Bivalve and Middle Township, researchers are working with oyster farmers to rebuild the oyster beds and find new ways to cultivate strains of oysters that will flourish and help rejuvenate the waters of the Delaware Bay.

“What we’re working with today is a much smaller natural population, but we’re also working with oyster farmers that are doing oyster farming in a different way,” said Daphne Munroe, an associate professor in shellfish ecology for Rutgers at the Haskins lab in Middle Township. “It’s bringing back the oysters in a new way to the Delaware Bay.”

Oyster farming may conjure up thoughts of producing Frankenstein strains of oysters in test tubes, but it’s much simpler than that. Tiny oysters are bred in a controlled setting, much like fish hatcheries, and grown to a size that can be released onto the beds of the bay to grow large enough to be harvested and eventually served on a bed of ice with cocktail sauce.

At low tide, oyster technicians scurry out on the muddy flats of the bay with nets containing thousands of tiny oysters strategically placed in rows to grow until they are moved to larger nets.

The different strains of oysters are monitored to keep track of which of the bivalves is more resistant to the environment.

One of the rewards for the oyster farmer is seeing cleaner water in the bay as the result of the natural filtering that oysters perform. And with that cleaner water comes new life in the form of aquatic species and insects that were killed by pollution in the past.

“Our oyster farmers are very interested in a healthy ecosystem,” said Monroe. “Their business model relies on it.”

Of all the food production systems we know today, she said, shellfish aquaculture is one of the most sustainable and “green.” They help buffer shorelines, filter water and provide other environmental benefits without putting any chemicals or food into the water.

“As far as the carbon footprint of this food production system, it is number one, the least impactful that we have today,” Monroe said.

Oyster farmer Joe Moro, of North Cape May in Lower Township, who grows oysters by the brand name “Naked Salts,” believes the oysters harvested from the Delaware Bay are some of the best in the market.

“If we keep on going at the pace we are going,” Moro said, “we will probably, in about four or five years, get the market back that it was in the ‘30s or ‘40s before the disease.”

“When people eat oysters at a restaurant, they are making a choice for sustainability,” said Monroe. “They’re choosing a product that is grown locally, that relies on clean water, and that while it was in the water helps improve the quality of the coastal ecosystem. And they’re good for you.”

This story was produced in collaboration with the New Jersey Sustainability Reporting Hub project. It was originally reported by Vernon Ogrodnek for the Press of Atlantic City, and may be re-distributed through the Creative Commons License, with attribution.